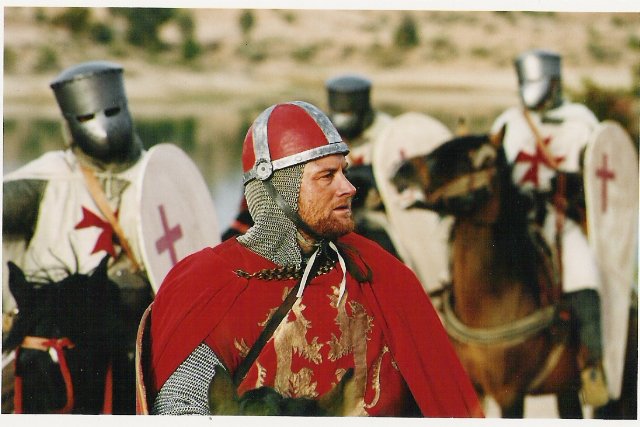

Richard the Lionheart and the Knights Templar

Summary

This account of King Richard the Lionheart’s experiences with the Knights Templar during the Crusades was based on a journal attributed to Geoffrey de Vinsauf, who accompanied King Richard on his expedition. It was documented in the 1842 book by Charles G. Addison, a member of the Inner Temple, which is now an association of barristers in London.

_______________________

In the mean time a third crusade had been preached in Europe. William, archbishop of Tyre, had proceeded to the courts of France and England, and had represented in glowing colors the miserable condition of Palestine, and the horrors and abominations which had been committed by the infidels in the holy city of Jerusalem. The English and French monarchs laid aside their private animosities, and agreed to fight under the same banner against the infidels, and towards the close of the month of May, in the second year of the siege of Acre, the royal fleets of Philip Augustus and Richard Coeur de Lion floated in triumph in the bay of Acre. At the period of the arrival of king Richard the Templars had again lost their Grand Master, and Brother Robert de Sablé or Sabloil, a valiant knight of the order, who had commanded a division of the English fleet on the voyage out, was placed at the head of the fraternity.[1] The proudest of the nobility, and the most valiant of the chivalry of Europe, on their arrival in Palestine, manifested an eager desire to fight under the banner of the Temple. Many secular knights were permitted by the Grand Master to take their station by the side of the military friars, and even to wear the red cross on their breasts whilst fighting in the ranks.

The Templars performed prodigies of valor; “The name of their reputation, and the fame of their sanctity,” says James of Vitry, bishop of Acre, “like a chamber of perfume sending forth a sweet odor, was diffused throughout the entire world, and all the congregation of the saints will recount their battles and glorious triumph over the enemies of Christ, knights indeed from all parts of the earth, dukes, and princes, after their example, casting off the shackles of the world, and renouncing the pomps and vanities of this life and all the lusts of the flesh for Christ’s sake, hastened to join them, and to participate in their holy profession and religion.”[2]

On the morning of the twelfth of July, six weeks after the arrival of the British fleet, the kings of England and France, the christian chieftains, and the Turkish emirs with their green banners, assembled in the tent of the Grand Master of the Temple, to treat of the surrender of Acre, and on the following day the gates were thrown open to the exulting warriors of the cross. The Templars took possession of three localities within the city by the side of the sea, where they established their famous Temple, which became from thenceforth the chief house of the order. Richard Coeur de Lion, we are told, took up his abode with the Templars, whilst Philip resided in the citadel.[3]

When the fiery monarch of England tore down the banner of the duke of Austria from its staff and threw it into the ditch, it was the Templars who, interposing between the indignant Germans and the haughty Britons, preserved the peace of the christian army.[4]

During his voyage from Messina to Acre, King Richard had revenged himself on Isaac Comnenus, the ruler of the island of Cyprus, for the insult offered to the beautiful Berengaria, princess of Navarre, his betrothed bride. The sovereign of England had disembarked his troops, stormed the town of Limisso, and conquered the whole island; and shortly after his arrival at Acre, he sold it to the Templars for three hundred thousand livres d’or.[5]

During the famous march of Richard Coeur de Lion from Acre to Ascalon, the Templars generally led the van of the christian army, and the Hospitallers brought up the rear.[6] Saladin, at the head of an immense force, exerted all his energies to oppose their progress, and the march to Jaffa formed a perpetual battle of eleven days. On some occasions Coeur de Lion himself, at the head of a chosen body of knights, led the van, and the Templars were formed into a rear guard.[7] They sustained immense loss, particularly in horses, which last calamity, we are told, rendered them nearly desperate.[8]

The Moslem as well as the christian writers speak with admiration of the feats of heroism performed. “On the sixth day,” says Bohadin, “the sultan rose at dawn as usual, and heard from his brother that the enemy were in motion. They had slept that night in suitable places about Caesarea, and were now dressing and taking their food. A second messenger announced that they had begun their march; our brazen drum was sounded, all were alert, the sultan came out, and I accompanied him: he surrounded them with chosen troops, and gave the signal for attack.” … “Their foot soldiers were covered with thick-strung pieces of cloth, fastened together with rings so as to resemble coats of mail. I saw with my own eyes several who had not one or two but ten darts sticking in their backs! and yet marched on with a calm and cheerful step, without any trepidation!”[9]

Every exertion was made to sustain the courage and enthusiasm of the christian warriors. When the army halted for the night, and the soldiers were about to take their rest, a loud voice was heard from the midst of the camp exclaiming, “Assist the Holy Sepulchre,” which words were repeated by the leaders of the host, and were echoed and re-echoed along their extended lines.[10] The Templars and the Hospitallers, who were well acquainted with the country, employed themselves by night in marauding and foraging expeditions. They frequently started off at midnight, swept the country with their turcopoles or light cavalry, and returned to the camp at morning’s dawn with rich prizes of oxen, sheep, and provisions.[11]

In the great plain near Ramleh, when the Templars led the van of the christian army, Saladin made a last grand effort to arrest their progress, which was followed by one of the greatest battles of the age. Geoffrey de Vinisauf, the companion of King Richard on this expedition, gives a lively and enthusiastic description of the appearance of the Moslem array in the great plain around Jaffa and Ramleh. On all sides, far as the eye could reach, from the sea-shore to the mountains, nought was to be seen but a forest of spears, above which waved banners and standards innumerable. The wild Bedouins,[12] the children of the desert, mounted on their fleet Arab mares, coursed with the rapidity of lightning over the vast plain, and darkened the air with clouds of missiles. Furious and unrelenting, of a horrible aspect, with skins blacker than soot, they strove by rapid movement and continuous assaults to penetrate the well-ordered array of the christian warriors. They advanced to the attack with horrible screams and bellowings, which, with the deafening noise of the trumpets, horns, cymbals, and brazen kettle-drums, produced a clamor that resounded through the plain, and would have drowned even the thunder of heaven.

The engagement commenced with the left wing of the Hospitallers, and the victory of the Christians was mainly owing to the personal prowess of King Richard. Amid the disorder of his troops, Saladin remained on the plain without lowering his standard or suspending the sound of his brazen kettle-drums, he rallied his forces, retired upon Ramleh, and prepared to defend the road leading to Jerusalem. The Templars and Hospitallers, when the battle was over, went in search of Jacques d’Asvesnes, one of the most valiant of King Richard’s knights, whose dead body, placed on their spears, they brought into the camp amid the tears and lamentations of their brethren.[13]

The Templars, on one of their foraging expeditions, were surrounded by a superior force of four thousand Moslem cavalry; the Earl of Leicester, with a chosen body of English, was sent by Coeur de Lion to their assistance, but the whole party was overpowered and in danger of being cut to pieces, when Richard himself hurried to the scene of action with his famous battle-axe, and rescued the Templars from their perilous situation.[14] By the valor and exertions of the lion-hearted king, the city of Gaza, the ancient fortress of the order, which had been taken by Saladin soon after the battle of Tiberias, was recovered to the christian arms, the fortifications were repaired, and the place was restored to the Knights Templars, who again garrisoned it with their soldiers.

The Templars, on one of their foraging expeditions, were surrounded by a superior force of four thousand Moslem cavalry; the Earl of Leicester, with a chosen body of English, was sent by Coeur de Lion to their assistance, but the whole party was overpowered and in danger of being cut to pieces, when Richard himself hurried to the scene of action with his famous battle-axe, and rescued the Templars from their perilous situation.[14] By the valor and exertions of the lion-hearted king, the city of Gaza, the ancient fortress of the order, which had been taken by Saladin soon after the battle of Tiberias, was recovered to the christian arms, the fortifications were repaired, and the place was restored to the Knights Templars, who again garrisoned it with their soldiers.

As the army advanced, Saladin fell back towards Jerusalem, and the vanguard of the Templars was pushed on to the small town of Ramleh.

At midnight of the festival of the Holy Innocents, a party of them sallied out of the camp in company with some Hospitallers on a foraging expedition; they scoured the mountains in the direction of Jerusalem, and at morning’s dawn returned to Ramleh with more than two hundred oxen.[15]

When the christian army went into winter quarters, the Templars established themselves at Gaza, and King Richard and his army were stationed in the neighboring town of Ascalon, the walls and houses of which were rebuilt by the English monarch during the winter. Whilst the christian forces were reposing in winter quarters, an arrangement was made between the Templars, King Richard, and Guy de Lusignan, “the king without a kingdom,” for the cession to the latter of the island of Cyprus, previously sold by Richard to the order of the Temple, by virtue of which arrangement, Guy de Lusignan took possession of the island and ruled the country by the magnificent title of emperor.[16]

When the winter rains had subsided, the christian forces were again put in motion, but both the Templars and Hospitallers strongly advised Coeur de Lion not to march upon Jerusalem, and the latter appears to have had no strong inclination to undertake the siege of the holy city, having manifestly no chance of success. The English monarch declared that he would be guided by the advice of the Templars and Hospitallers, who were acquainted with the country, and were desirous of recovering their ancient inheritances. The army, however, advanced within a day’s journey of the holy city, and then a council was called together, consisting of five Knights Templars, five Hospitallers, five eastern Christians, and five western Crusaders, and the expedition was abandoned.[17]

The Templars took part in the attack upon the great Egyptian convoy, wherein four thousand and seventy camels, five hundred horses, provisions, tents, arms, and clothing, and a great quantity of gold and silver, were captured, and then fell back upon Acre; they were followed by Saladin, who immediately commenced offensive operations, and laid siege to Jaffa. The Templars marched by land to the relief of the place, and Coeur de Lion hurried by sea. Many valiant exploits were performed, the town was relieved, and the campaign was concluded by the ratification of a treaty whereby the Christians were to enjoy the privilege of visiting Jerusalem as pilgrims. Tyre, Acre, and Jaffa, with all the sea-coast between them, were yielded to the Latins, but it was stipulated that the fortifications of Ascalon should be demolished.[18]

After the conclusion of this treaty, King Richard being anxious to take the shortest and speediest route to his dominions by traversing the continent of Europe, and to travel in disguise to avoid the malice of his enemies, made an arrangement with his friend Robert de Sablé, the Grand Master of the Temple, whereby the latter undertook to place a galley of the order at the disposal of the king, and it was determined that whilst the royal fleet pursued its course with Queen Berengaria through the Straits of Gibraltar to Britain, Coeur de Lion himself, disguised in the habit of a Knight Templar, should secretly embark and make for one of the ports of the Adriatic. The plan was carried into effect on the night of the 25th of October, and King Richard set sail, accompanied by some attendants, and four trusty Templars.[19]

On that journey King Richard was captured near Vienna by King Leopold V of Austria, with whom he had argued fiercely in the Holy Land. Richard was transferred to Leopold’s superior, the Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI. After ransom was paid, King Richard was released, and returned to England and France to live out the rest of his reign.

When Saladin captured the Templar fortress at Jacob’s ford on the river Jordan, “The fortress was reduced to a heap of ruins, and the enraged sultan, it is said, ordered all the Templars taken in the place to be sawn in two….”[20]

Notes:

Drawn from the book by Charles G. Addison The History of the Knights Templars, the Temple Church, and the Temple (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1842), pp. 141-149.

[1] Hist. de la maison de Sablé, liv. vi. chap. 5. p. 174, 175. Cotton MS. Nero, E. vi. p. 60. folio 466, where he is called Robert de Sambell. L’art de Verif. p. 347.

[2] Jac. de Vitr. cap. 65.

[3] Le roi de France ot le chastel d’Acre, ot le fist garnir et le roi d’Angleterre se herberja en la maison du Temple.—Contin. Hist. Bell. Sacr.apud Martene, tom. v. col. 634.

[4] Chron. Ottonis a S. Blazio, c. 36. apud Scriptores Italicos, tom. vi. col. 892.

[5] Contin. Hist. Bell. Sacr. apud Martene, tom. v. col. 633. Trivet, ad. ann. 1191. Chron. de S. Denis, lib. ii. cap. 7. Vinisauf, p. 328.

[6] Primariam aciem deducebant Templarii et ultimam Hospitalarii, quorum utrique strenue agentes magnarum virtutum praetendebant imaginem.—Vinisauf, cap. xii. p. 350.

[7] Ibi rex praeordinaverat quod die sequenti primam aciem ipse deduceret, et quod Templarii extremae agminis agerent custodiam.—Vinisauf, cap. xiv. p. 351.

[8] Deducendae extremae legioni praefuerant Templarii, qui tot equos eâ die Turcis irruentibus, a tergo amiserunt, quod fere desperati sunt.—Ibid.

[9] Bohadin, cap. cxvi. p. 189.

[10] Singulis noctibus antequam dormituri cubarent, quidam ad hoc deputatus voce magnâ clamaret fortiter in medio exercitu dicens, Adjuva sepulchrum sanctum; ad hanc vocem clamabant universi eadem verba repetentes, et manus suas cum lacrymis uberrimis tendentes in caelum, Dei misericordiam postulantes et adjutorium.—Vinisauf, cap. xii. p. 351.

[11] Ibid. cap. xxxii. p. 369.

[12] Bedewini horridi, fuligine obscuriores, pedites improbissimi, arcus gestantes cum pharetris, et ancilia rotunda, gens quidem acerrima et expedita.—Vinisauf, cap. xviii. p. 355.

[13] Vinisauf, cap. xxii. p. 360. Bohadin, cap. cxx.

[14] Expedite descenderunt (Templarii) ex equis suis, et dorsa singuli dorsis sociorum habentes haerentia, facie versâ in hostes, sese viriliter defendere coeperunt. Ibi videri fuit pugnam acerrimam, ictus validissimos, tinniunt galeae a percutientium collisione gladiorum, igneae exsiliunt scintillae, crepitant arma tumultuantium, perstrepunt voces; Turci se viriliter ingerunt, Templarii strenuissime defendunt.—Ibid. cap. xxx. p. 366, 367.

[15] Vinisauf, cap. xxxii. p. 369.

[16] Ibid. cap. xxxvii. p. 392. Contin. Hist. Bell. Sacr. apud Martene, v. col. 638.

[17] Vinisauf, lib. v. cap. 1, p. 403. Ibid. lib. vi. cap. 2, p. 404.

[18] Ibid. cap. iv. v. p. 406, 407, &c. &c.; cap. xi. p. 410; cap. xiv. p. 412. King Richard was the first to enter the town. Tunc rex per cocleam quandam, quam forte prospexerat in domibus Templariorum solus primus intravit villam.—Vinisauf, p. 413, 414.

[19] Contin. Hist. Bell. Sacr. apud Martene, tom. v. col. 641.

[20] Addison, Charles G. The History of the Knights Templars, the Temple Church, and the Temple (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1842), pp. 77-78.