Within a week of the Muslim victory at Hattin on July 4, 1187 the port city of Acre had surrendered to Saladin’s army. Within a month Toron, Sidon, Gibelet and Beirut had also capitulated as the famed warrior made his way down the Palestinian coast before marching on Jerusalem, which surrendered on October 2.

Although it had taken the Muslim army a short time to capture Acre, it would take the Christian armies nearly two years to take it back – from August 28, 1189 until July 12, 1191. The victory was finally earned for Christendom by King Richard I (The Lionheart) who had taken control of the campaign a month earlier after arriving from the west.

Both Saladin and Richard were strong willed military men, a point of stubbornness that led to Richard’s execution of 2,700 Muslim prisoners over a ransom dispute.

But the story of the capture of Acre by Richard I is a story for another instalment of this series. What we will be dealing with in this edition is the lesser-known Battle of Arsuf, a conflict that both the Templars and the Hospitallers were involved in alongside the English king.

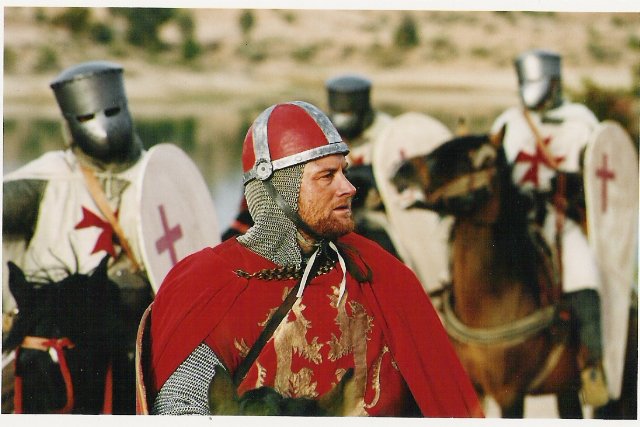

Two days after the massacre at Acre, Richard set off with his army for Jaffa. His goal was Jerusalem, but it would first be necessary to capture the port city as a base of operations. As the army marched down the coast they stayed close to the shoreline to benefit from the cool breeze and the support of the ships that followed the march down the coastline. The army was divided into three columns. The first was comprised of knights, and kept to the shore, while the remaining two columns, made up of infantrymen, took the landside position. In the vanguard were the Templars, whom King Richard relied on throughout his crusade. In fact it had been through his influence that Robert de Sablé, an Angevin who had travelled east with the king, had been elected to succeed de Ridefort as Master of the Order, despite the fact that de Sablé was not a Templar when he left England.

As the crusader army marched down the coast their movement was shadowed by Saladin’s light mounted archers who launched a series of attacks on the Christians, riding in close enough to shoot and then retreating again as quickly as they had come. Despite the torments of Saladin’s arrows, the army managed to maintain their discipline and the crusader infantry, armed with crossbows, took out a number of the Muslim archers.

Although the knights and their heavy charge often receive the bulk of attention in discussions of medieval conflicts, the discipline of the infantry is every bit as worthy of mention. For while the knights were cooled by the sea breeze and protected by two lines of human targets, the infantrymen in those lines sacrificed their lives to protect their nobly born counterparts and their horses. The medieval war horse was the tank of its day and the loss of even one horse was a great cost to an army. It is for this reason that the Templar Rule went to such lengths to ensure that no harm would come to them.

After two weeks of marching, Richard’s army had covered less than half the distance to Jaffa and on September they passed through a wooded area about 10 miles north of Arsuf. Although they had been tormented throughout the march, the Muslims had inflicted little real damage. That would all change the next morning.

On September 7, as the crusaders began their march towards Arsuf, Saladin began his march towards victory. Throughout the morning the Muslims assaulted the Christians using the tactics they had employed throughout the march. However, just before noon they began a fully fledged assault. The crusaders continued to resist their attacks, once again thanks to the discipline of the common foot soldiers. Between the Muslims and the knights were two rows of infantrymen. The front line knelt with spear and shield, while the crossbowmen returned the attack. When the crossbowmen rearmed, the spearman stood with their shields to provide their counterparts with cover.

Meanwhile the knights were aligned in battle formation behind the front line. The Templars were at the southern end of the line forming the right flank along with the Bretons, Angevins and King Guy of Lusignan and his party. King Richard and his English and Normans troops made up the centre assisted by Flemish and French troops. In the rearguard were the Hospitallers. In total the crusader army was made up of approximately twelve hundred knights and ten thousand infantrymen, while the Muslims numbered twenty thousand men equally split between cavalry and infantry.

As the day progressed it became increasingly difficult for the infantrymen to maintain a line. The Muslim attacks came closer and closer, ultimately close enough to replace their bows and arrows with lances and swords. Soon the Christian infantry were falling in increasing numbers.

Hoping to draw the crusaders into an early charge, Saladin’s troops focused their attacks on the Hospitallers’ division. The attacks began to take their toll on the Hospitallers and on several occasions Garnier of Nablus, the Master of the Order, approached King Richard begging him to give the signal to charge, but Richard continued to urge patience. Finally the Muslim assaults proved too much and the Marshal of the Order and one of his knights broke rank and began the charge. Although the signal had not been given, all the Hospitallers assumed it had and charged after their comrades. Within seconds horses were spurred down the Christian line as knight after knight joined the heavy cavalry charge.

Richard, seeing that there was no choice but to join the battle lest those who were already in it be slaughtered, ordered the Templars, as well as the Bretons and Angevins in their line to attack Saladin’s left flank. Finally the Templars were able to release the frustration that the Hospitallers had been unable to contain and their charge drove the Saracens from the field, stunned by the Hospitallers impetuousness and mopped up by the Templars’ discipline. Although the losses had been relatively light on both sides of the field of battle, the Muslims had been repelled and, following so close on the capture of Acre, the battle must have been a morale-boosting victory for the Christians in general and the Templars in particular. It had been the first open battle since the Battle of Hattin four years earlier and the Templars would not have forgotten the role their Order played there.

In October of 1191, King Richard wrote to the Cistercian abbot of Clairvaux informing him of the success of his crusade:

“With God’s guidance we reached Jaffa on 29 September, 1191 and fortified the city with ditches and a wall with the intention of protecting the interests of Christianity to the best of our ability. After his defeat [at Arsuf] Saladin has not dared to face the Christians, but like a lion in his den has been secretly lying in hiding and plotting to kill the friends of the Cross like sheep for slaughter.

“So when he heard that we were swiftly heading for Ascalon, he overthrew it and levelled it to the ground. Likewise he had laid waste and trampled on the land of Syria.”

Soon after writing to the abbot, Richard entered into negotiations with both the Templars and Saladin; with the former it was over the purchase of Cyprus, while with the latter it was over the surrender of Jerusalem.